Plantations, Preservation, and Privilege in New Orleans

This is the first of a series of essays on items of historical interest related to New Orleans. I studied fine arts, and after moving to New Orleans studied historic preservation and architecture conservation. I interned with Save Our Cemeteries for a year learning masonry and conservation skills. I work now on historic masonry structures, mostly but not exclusively in cemeteries. I read and think a lot about history, and also have mixed feelings about the many different aspects of preservation work and how it can affect people and communities. My goal is basically to write an opinion column with historical interest.

Something that’s been in the news lately is the proposed removal of statues of confederate political figures, and I couldn’t help but compare it to other historical sites that I’ve visited and worked on in Louisiana. Romanticization of the confederate era is common here, not just with statues and street names, but just as blatantly with the plethora of plantations that are such a huge draw to visitors. As a student studying historic preservation, I visited a lot of these plantations. These trips were intended not as history lessons, but as tutorials in the many different ways historic properties can be treated, and what it will mean to visitors who may not have a historical background on the site.

Plantations are examples of beautiful architecture, and irreplaceable monuments to the past, but they are also symbols of slavery and brutal oppression. There are many restored plantations one can tour in the New Orleans area, with almost as many different approaches to this topic. One extreme example is the Destrehan Plantation, which avoids the topic of slavery entirely, despite the fact that one of the biggest pre-civil war slave revolts happened there. The revolt was suppressed and the heads of the dissenters were put on stakes on the banks of the Mississippi River so slaves being brought south would be warned the wages of revolt. The Destrehan Plantation is beautifully restored and does have an interesting workshop on folk medicine used by slaves, but if you’re looking for historical sensitivity you will be dismally disappointed. Expect shocking references to “servants”, and self-indulgent period costumes.

The Laura Plantation tour is very thoughtful, and if you’re interested in carpentry and craftsmanship it is wonderful. The restoration and tour material are based upon the diaries of a woman who grew up on the plantation just before the civil war, and include her thoughts on the cruelty and injustice of slavery. I also appreciated that they showcase the skills of the Africans who built the structures on the plantation. A vast majority of Africans brought to Louisiana originated from the Senegal-Gambia region, an area that has a similar climate to Louisiana, and had knowledge of how to build in such an environment. They knew how to fell and mill lumber, build foundations in the swamp, sink pilings, and design houses that maximize airflow. If it wasn’t for these skills, it’s doubtful the French colonists would have survived in the miserable fetid swamp we now call home.

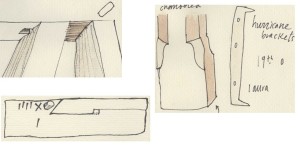

Sketches of architectural details at Laura, including marks that were used to measure floor beams

As a last comparison, the Whitney plantation opened in 2014 as the first Louisiana plantation tour with a focus specifically on slavery. It’s thoughtfully restored buildings include many outbuildings and slave quarters, as well as hundreds of first person slave narratives. There are also beautiful sculptures and memorials installed throughout the property as monuments to those who died there. This conceptual approach is the other extreme in plantation preservation, and perhaps signals a new trend in the preservation field of being historically honest and inclusive.

The experience of doing restoration work on a working plantation is another experience entirely. I recently worked on a building on the property of a sugar plantation that has been in continuous operation since before the Civil War. We repointed and rebuilt part of a brick building dating to around the 1830’s, and spent many many hours on the property. The sugar mill, within eyesight of the building we were restoring, operates year round as it has for nearly 200 years. The sense of history being frozen on places such as this is eerie. It would appear there was a seamless transition over generations from slave to sharecropper, sharecropper to minimum wage worker, all in the same tiny community, all gazed over impassively by gilded portraits of the French ancestors.

Repointing bricks on the roof of a historic building on a plantation

These paradigms are taken for granted in small towns all over the south, but when a building, property, or statue is preserved and opened up to the public it becomes not just a remnant of history, but an intentional symbol. People working in a historical field should feel obligated to ask themselves: what exactly are these places intended to be symbols of? One thing they seem to fulfill is the timeless desire of the middle class to see the lavish opulence the rich lived in, often without much thought to the way these families gained their wealth. After all, something that is often forgotten on many of the plantation tours, in the midst of the mahogany furniture and chandeliers, is that these places only ever existed to produce an agricultural product, albeit a complete luxury item.

A cane field in Southwestern Louisiana

As around America, including in New Orleans, confederate statues are being retired because of the painful history they symbolize, it may likewise be time to think about how we approach all of our local history. All history is haunted. And all history should be preserved, even if it’s painful. Especially if it’s painful. If we destroyed everything symbolizing something we wanted to forget, we wouldn’t have the reminders we need to prevent history from repeating itself. And these buildings, just like the controversial confederate statues, were created by skilled craftsmen who deserve to have their work preserved. Memento Park in Budapest represents one approach to this controversial subject. The open air park is filled with statues of Communist leaders that were pulled down by the populace after the end of the era. A quote by the architect on the project: “This park is about dictatorship. And at the same time, because it can be talked about, described, built, this park is about democracy. After all, only democracy is able to give the opportunity to let us think freely about dictatorship.”

Destrehan Plantation: 13034 River Road, Destrehan, LA. (985) 764-9315

Laura Plantation: 2247 Highway 18, Vacherie, LA 70090. (225) 265-7690

Whitney Plantation: 5099 Highway 18, Wallace, LA 70049. (225) 265-3300\

http://bayoupreservationllc.com/

https://sitkahistory.com/

Preserving buildings that existed pre-Civil War and being honest about their history is very different than the push to preserve statues built post-Civil War solely to honor seditionists whose noteworthy accomplishments were fighting to preserve the enslavement of other humans. I’m not sure what is so difficult to understand about that, and you are an educated woman so this concept shouldn’t be hard to grasp, but I’ve noted that it’s a problem mostly limited to white folks whose recent family histories don’t include enslavement and murder of their ancestors.

If you feel that strongly that these Confederate statues, whose only purpose was to strike fear in the hearts of former slaves and enshrine men who fought and died to keep slavery a way of life, should be preserved, then let them be removed to a museum, where those who wish to look upon them can choose to do so. But they have no place adorning public squares where everyone is forced to look upon these monuments to treason and brutality.

Hi Emily- it appears you have had a serious misunderstanding. I absolutely support the removal of Confederate statues from public places, always have, and nowhere did I suggest otherwise. In the article I even mentioned Memento Park in Budapest as an example of just what you suggest- that these statues of men who symbolize brutality be removed to a museum setting where they are placed in a historical context. I think the ongoing removal of Confederate statues presents us with an opportunity to think about how we approach all of our local history, specifically the racist presentation of history at some plantation museums. I briefly brought up the removal of these statues as a positive example of change I hope to see more widely in history and preservation. May I suggest you try to actually read my article?