Who’s Really Buried in Maire Laveau tomb? Her Legacy, and Her Tomb

I first learned about Marie Laveau through American Horror Story with Angela Bassett starring as the legendary Voodoo priestess in season 3. The only thing I knew about Marie Laveau was that she was a real person, but beyond that, I only knew what I saw on screen and from myths and fiction. How much of it is accurate, though? Even almost 140 years after her death, Marie Laveau continues to capture people’s imaginations. Those who visit New Orleans are more than likely to hear about her myth and expect to see voodoo influences around the historic city. People often flock to Marie Laveau’s tomb in St. Louis Cemetery no. 1. It has become such an issue because people often vandalize it. There isn’t much in terms of written records, and much of what is “known” of Maire Laveau evolved from accounts and writings that happened after her death in 1881. Maire Laveau continues to capture people’s imaginations today, even 140 years after her death. We will look at some of the myths and realities surrounding the Voodoo Queen, why her legacy still captures people’s imaginations, and the mystery surrounding her tomb in St. Louis Cemetery no. 1.

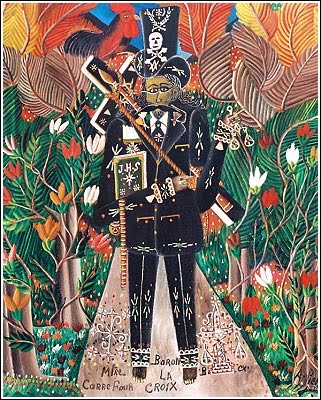

Before delving further into Marie Laveau’s life, we should quickly glance at what voodoo is and how it plays such a huge part in New Orleans’s identity. Louisiana Voodoo has influences from West African religion, Roman Catholicism, and Haitian Vodou (“Louisiana Voodoo”). Louisiana Voodoo originated in New Orleans and was cultivated by enslaved West Africans. But according to Mary A. McAlister, Voodoo is more than just a religion and also encompasses other aspects of philosophy, medicine, and justice. McAlister goes on to summarize:

The unseen world is populated by lwa (spirits), mystè (mysteries), anvizib (the invisibles), zanj (angels), and the spirits of ancestors and the recently deceased. All these spirits are believed to live in a mythic land called Ginen, a cosmic “Africa.” The God of the Christian Bible is understood to be the creator of both the universe and the spirits; the spirits were made by God to help him govern humanity and the natural world (McAlister).

One of the reasons it continues to capture people’s imaginations is the secret nature of religion. There is no direct governing body of Voodoo, and is rarely spoken about to people who are considered “outsiders” (“Louisiana Voodoo”). It is typically an oral tradition passed down from generation to generation through stories and spoken word (McAlister). This oral tradition, along with some key concepts and beliefs that have been romanticized in popular culture over the years, captures people’s imaginations. Zora Neale Hurston, a famous African-American author, whose own imagination was enthralled by Voodoo and allegedly underwent a Voodoo ritual of her own. Today, the spirit of voodoo continues to enthrall yearly visitors. If people are interested in learning about Voodoo, you can visit the Voodoo Museum located in the French Quarter.

You can also learn more on a Voodoo Tour with Nola Tour Guy.

Some of the myths that voodoo has been romanticized about are things like zombies and spiritual possession. Unlike how it has been portrayed in movies like The Skeleton Key, spiritual possession in voodoo is meant to be part of larger practice in the religion. Mary McAlister explains, “The primary goal and activity of Vodou is to sevi lwa (“serve the spirits”)—to offer prayers and perform various devotional rites directed at God and particular spirits in return for health, protection, and favour.” This presents an image contrary to the concept popularized by Hollywood. Another aspect is zombies. While zombies have been illustrated as the undead complete with decaying flesh and a craving for brains, the reality is quite the opposite. According to the article “Zombi,” the truth is that zombies are living individuals who are heavily drugged from various substances. This is an example of how pop culture has twisted the reality of voodoo. We’ve learned to think of voodoo as some otherworldly and mystical force capable of magical feats and mysticism, but there is more than meets the eye. Maire Laveau’s legacy found itself in a similar situation after her death, even when it came to her final resting place.

When Marie Laveau was born, there was no monumental shifting of the Earth or raising the seas. The real Maire Laveau was born sometime around 1801. There is no exact date of her birthday. Shantrelle Lewis records that “[s]ome documents indicate that she was born in 1794, while other research supports 1801 as the year of her birth…[and it is also] said [she is] to have been born to an African woman, named Marguerite Decantel, and Charles Laveau.” There is not much written about her childhood regarding official records; however, she begins to grow into her own person into adulthood. Like many, Marie Laveau was Catholic and was of high standing within the Catholic community (Ward 28). Martha Ward, in Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau, explains:

Although French royal policy and the Code Noir or “Black Laws” of 1724 instructed European Catholics to baptize newly arrived Africans as soon as possible, there were no seminaries and too few priests to provide spiritual direction or religious education in Louisiana. The only Catholics to answer the call to educate Africans and Creoles in matters of faith were a group of privileged French Catholic women who arrived in the struggling colony in 1727— they designed and implemented the first educational system in Louisiana (29).

As a result, her association with the Catholic faith was expected. She learned much through the Ursuline Order at the Saint Louis Cathedral found today in Jackson Square. (If you want to visit Saint Louis Cathedral, you can learn more here). Ward points out that, like many others in her social class, “[Laveau] had learned the Catechism, a call and response, question and answer lesson about the principles of faith and spirituality, at the knees of the self-reliant nuns” (31). Laveau lived an ordinary life as a Catholic and a part of her community. She married her first husband in 1819, and he later died a short time later in 1820. There is some mystery surrounding the death of her first husband, but his passing is the commonly accepted truth. Later on, Laveau entered into a partnership with Christophe Dominick Duminy de Glapion, with whom they had 15 children, all baptized at Saint Louis Cathedral (“Maire Laveau”). She even became a hairdresser to support her family (Lewis). This allowed her to be exposed to “black clients who were house servants…[that allowed her to be] exposed to the personal information about wealthy white clients” that would later help her connections to the larger New Orleans community later on (Lewis).

When Maire Laveau ventured into Voodoo, her life shifted and changed. She was able to help the greater community than she previously had. In 1827, she ventured away from the Catholic faith, launched into her “lifelong apprenticeship” in voodoo, and began to live a double life with both religions (Ward 33). Before venturing into Voodoo, she allegedly had a connection to religion. According to Shantrelle P. Lewis, Laveau had familial ties following her mother’s death. Laveau became known for her ability to advise regarding “marital affairs, domestic disputes, judicial issues, childbearing, and fiancés, health, and good luck” (Lewis). She was also known for supplying magical objects and services like “protective… [things such as] candles, powder, and an assortment of other items mixed together to create a gris-gris” (Lewis). She became well known throughout New Orleans and a community pillar through her services and work through her Catholic and Voodoo connections.

Despite Marie Laveau’s reputation developing as a voodoo priestess and later queen, during her lifetime, and throughout her community, there was not much published about it (Long “Marie Laveau” 279). Voodoo (also spelled voudou) was part of enslaved African Americans and was often associated with the “‘illegal assembly of slaves and free persons’” (Long “Maire Laveau” 279). This likely could have added to the urgency and secrecy that voodoo is reputed to have, in addition to what has already been mentioned. In 1850, Carolyn Long describes “the summer crackdown of 1850,” where during June and July that year, local authorities conducted raids “arresting female slaves, free women of color, and white women on charges of illegal assembly” (“Maire Laveau” 280; 279). Laveau wasn’t arrested during this; however, she did complain to the local authority about a statue taken from her (“Marie Laveau” 280). Laveau reappeared in local newspapers that described court appearances and her connections to voodoo towards the end of the 1850s, but none of this resembled the stories that would follow her after her death (“Maire Laveau” 281). Long notes that local newspapers continued to cover Laveau and her voodoo practices, especially during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. On June 9, 1869, Laveau’s name appeared in the local paper Commercial Bulletin in an article announcing her retirement as Voodoo Queen. The paper wrote, “‘This season is marked by the coronation of a new voodoo queen in the place of the celebrated Marie Laveau, who has held her office for more than a quarter of a century and is now superannuated in her seventieth year’” (Voodooism” Commercial Bulletin, June 25, 1869, qtd. in Long “Marie Laveau” 282). Even after Laveau retreated from being a voodoo queen, she still remained active in the community and charities due to her Catholic faith (“Maire Laveau” 287). It wasn’t until her death in 1881 did newspapers begin to really publicize her reputation as a voodoo queen.

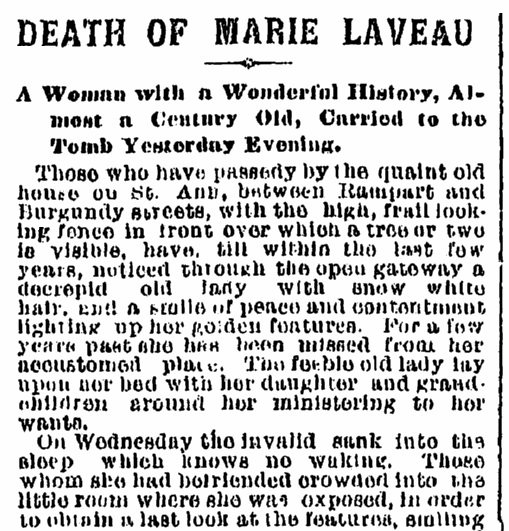

Marie Laveau died on June 15, 1881. The New York Times, on June 23, 1881, published a lengthy obituary regarding her “as a dealer in the black arts and a person to be dreaded and avoided” (2). However, the obituary also highlights Laveau’s “healing knowledge” and where “her advice was oft-times really valuable and her penetration remarkable” along with “the gift of great beauty…[that] no wonder that she possessed large influence in her youth and attracted the attention of Louisiana’s men and most distinguished visitors”(2). The obituary paints a contradicting picture. The obituary also touches on the rest of Marie Laveau’s life, concluding with her burial in St. Louis #1 cemetery. The New York Times states:

The secrets of her life, however, could only be obtained from the old lady herself, but she would never tell the smallest part of what she knew, and now her lips are closed forever, and as she could neither read nor write, not a scrap of evidence is left to chronicle her exciting life (2).

In “Marie Laveau: A Nineteenth-Century Voudou Priestess,” Carolyn Long attempted to try and gather what was published on the legendary woman to make a cohesive tale. She notes that opinions on Laveau were divided and included rejections of the idea she was a real voodoo priestess despite her contributions to the community. At the same time, other sources cited her as having “‘drunken orgies on the bayou’” with her followers (264). Even after her death, she still captured people’s imaginations in today’s pop culture. An example of this is how the icon of the voodoo priestess became a black archetype. Another example of Maire Laveau capturing people’s interests is seeing reimagined characters reappear in season three of American Horror Story in New Orleans.

While it is recorded that Marie Laveau is buried in St. Louis Cemetery no. 1, New Orleans’s oldest cemetery, there are some challenges to this accepted notion. Long notes that through the efforts of the Louisiana Writers Project, some of the older residents of New Orleans that they interviewed recorded that Laveau was buried in St. Louis Cemetery #2 instead (287). St. Louis no. 1 cemetery is the oldest cemetery located in the city and characterized by raised tombs and is known collectively as one of the “Cities of the Dead.” St. Louis no. 2 Cemetery also has raised tombs and is home to many famous blues and jazz musicians. However, St. Louis no. 2 Cemetery also contains the “‘Wishing Vault’…[and today] both gravesites are visited by devotees who draw cross marks on the marble and slabs and leave offerings” (Long “Marie Laveau” 288). The purpose of drawing x’s in voodoo symbolizes wish making and giving. It has become commonplace by visitors in the past to mark the recorded gravesite of Marie Laveau with three x’s. However, this is considered vandalism, and there is an etiquette to follow when visiting cemeteries. As a result, St. Louis no. 1 banned tourists after repeated vandalism of the crypts. Today, one solo company offers tours to New Orleans’s oldest cemetery. In addition to Maire Laveau’s resting place in St. Louis Cemetery no. 1, there are still rumors that she may also be buried (at one time or another in St. Louis Cemetery no. 2), at a location known as the “Wishing Valut.” In the lecture “The Tomb of Marie Laveau in St. Louis Cemetery no.1,” the writer notes that there is evidence from a map from 1937 with three wall tombs along with an Iberville wall labeled “Maire Laveau” or “daughter” (Long “The Tomb” 12). This is one piece of “proof,” however, this resting place doesn’t belong to Maire Laveau. This fascination doesn’t stop people from visiting and occasionally putting offerings, prayers, and even marking the tombs with x’s.

But why would people continue to visit and mark up Marie Laveau’s tomb? What is it that captures people’s imaginations? While the actual funeral was held in St. Louis no. 1, other testimonies suggest she is buried elsewhere. The Louisiana Writers’ Project uncovered this during the 1940s through interviews. However, one thing that is commonly overlooked is who is actually buried in the tomb. Due to the sensationalism of Laveau’s life after her death and the mystery surrounding voodoo, there has been a lot of speculation over the decades. In truth, more than 84 people are interred in Maire Laveau’s St. Louis no. 1 tomb (Bruno). In a lecture titled “The Tomb of Marie Laveau in St. Louis Cemetery no.1,” Caryoln Morrow Long observes that in addition to being a voodoo priestess, Laeveu’s Catholic faith was also important to her character. Marie Laveau embodies one specific aspect of the Catholic Church, which was, “Corporal Works of Mercy, in which the faithful are instructed to “feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, shelter the homeless, visit the sick, visit the imprisoned, and bury the dead” (Long “The Tomb” 2). Her charitable giving also continued to help others in death. It wasn’t uncommon for multiple people to be buried in familial tombs, and this was no exception for Laveau and her tomb. Of the 84 that call Laveau’s tomb their final resting place, 25 family members (including children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren), 7 family members, and 6 neighbors (Bruno). It wasn’t uncommon for multiple people to be buried in a single tomb which became part of the characteristics of how the city buried their dead, which defined New Orleans’s “Cities of the Dead.” However, who were these people? Why are they buried there? Stephanie Bruno concludes that this was an extension of Maire Laveau’s generous nature. After Laveau died in 1881, the media cast her as a mysterious voodoo figure from the Louisiana bayous. In truth, contrasting the accounts, Maire lived her life in service to her community. Laveau “ministered to the sick…comforted prisoners on death row…[and even] sponsored an orphan” (Bruno). This service extended into death, where “when someone died, she was all too willing to lease space in her family tomb (likely built in the 1830s) or lend a spot to someone awaiting placement somewhere else” (Bruno). Marie Laveau’s tomb was an extension of her giving and charitable personality instead of a shrine to some mysterious ritual.

Marie Laveau captured people’s imaginations after her death in 1881. Even today, people continue to visit her tomb. There is more, though, to Marie Laveau. Her tomb houses more than just her in death, but multiple people. She was more than a voodoo priestess. Her tomb stands as a final testament to her generous and charitable nature to people and the city of New Orleans.

This is the only tour that enters St Louis #1

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. “Zombi.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 30 Aug. 2018.

https://www.britanca.com/topic/zombi. Accessed 13 May 2022.

Bruno, Stephanie. “How many have joined Marie Laveau in eternal slumber? Biographer says the famous Voudou queen made room in her landmark tomb for many.” NOLA.com, 3 Nov. 2015, https://www.nola.com/entertainment_life/article_006e44bc-c3ab-589c-9243-7ddc464d62f0.html. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Lewis, Shantrelle P. “Marie Laveau.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Jun 2021, https://www.britanca.com/biography/Marie-Laveau. Accessed 13 May 2022.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. “Marie Laveau: A Nineteenth-Century Voudou Priestess.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 46, no. 3, 2005, pp. 262–92, JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4234121. Accessed 10 May 2022.

—. “The Tomb of Marie Laveau in St. Louis Cemetery no. 1.” Academia, 23 Apr. 2019. https://www.academia.edu/38988979/The_Tomb_of_Marie_Laveau_in_St_Louis_Cemetery_No_1_a_lecture_sponsored_by_Save_Our_Cemeteries. Accessed 18 May 2022.

“Louisiana Voodoo.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 May 2022,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louisiana_Voodoo.

McAlister, Elizabeth A.. “Vodou”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Apr. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Vodou. Accessed 13 May 2022.

O’Reilly, Jennifer. “‘We’re More than Just Pins and Dolls and Seeing the Future in Chicken Parts’: Race, Magic and Religion in American Horror Story: Coven.” European Journal of American Culture, vol. 38, no. 1, Mar. 2019, pp. 29–41. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.proxy.lib.odu.edu/10.1386/ejac.38.1.29_1. Accessed 12 May 2022.

“THE DEAD VOUDOU QUEEN: MARIE LAVEAU’S PLACE IN THE HISTORY OF NEW-ORLEANS.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 23, 1881, p. 2. ProQuest. Web. 15 May 2022.

Ward, Martha. Voodoo Queen: the Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau. UP of Mississippi, 2004.

We are Dirt Co Media House & in route to New Orleans today. We are currently shooting a doc on a lady and need to know who we can tap as a viable resource to the behind the scenes true nitty gritty actual life of New Orleans. Not interested in the Touristy Stuff, we need someone who lives there knows the history in the French quarter and has access to the People with Old Roots and Heritage there. Voodoo, Jazz, Plantations, Cemeteries, Bayou specifically someone with a fan boat that will be okay with us filming. If you can help we will be arriving this evening and looking to meet and chat tomorrow morning. Please email or text or call Angel Douglas @ queensmith223@gmail.com or # 405.999.8084.

Salut ~ Angel

Dirt Co. Media House

Producer & Film Maker

angel@dirtcomedia.com

queensmith223@gmail.com

# 405.999.8084

I don’t have a fan boat. Hopefully you found someone!