Free Self Guided St. Louis #3 Cemetery Tour with map

The cemetery is located at 3421 Esplanade Avenue. Established in 1853 on the former site of a leper colony St Louis #3 was built as a response to the yellow fever epidemic of 1852. St. Louis #3 is in one of New Orleans’s oldest neighborhoods, Bayou St. John near the end of Esplanade Avenue.

The graves found in St. Louis #3 tend to be more elaborate and decorative with stunning examples of marble 19th-century tombs and crypts. You can see a bit of everything in the cemetery including family tombs, coping tombs, wall vaults and even more modern multi-burial mausoleums. There are also many tombs with architectural influences from Greek and Roman, Gothic, Egyptian, Baroque, and Byzantine made up of granite and pre-cast concrete. There is also a plethora of timeless sculptures that can be found throughout the cemetery. By the early 20th century, St. Louis #3 continued to grow with tombs from all walks of life being built by the city’s best architects. The first modern mausoleum, the St. Mark Memorial, was constructed in 1966. Since then, the St. Teresa Garden Mausoleum and the Serenity Garden Columbarium were added in 2015.

Easily accessible via the Canal Street car, check out the RTA’s Website for more info.

One of the most notable features in New Orleans cemeteries is the above-ground tombs. Unlike other major cities, New Orleans sits near the Mississippi River and has a high-water table. Historically, this made burying the dead a difficult task. The graves would often flood. To combat this, New Orleans residents built intricate tombs, raised above the water table. This solution helped combat the flood threats and the problems with digging in the river mud. The cultural practices of the French and Spanish initially influenced how the dead were honored. As the 19th progressed, cemeteries were planned out like city parks and people sought to honor their dead with elaborate memorials. These unique graves would later become a part of the iconic New Orleans that we see today

Would you like a GPS enabled audio tour of this cemetery? find out more about our audio tours here

Once you cross through the front gate look to your left. With no relation to the Tujanue in the French Quarter (the second oldest restaurant in the city). Check out the names and dates and you can see that there is no limit to how many burials can happen in one of these tombs. You can also look at the front of the tomb, look at the keyhole, you’ll notice most of these tombs have a little bolt.

Walk to your right. You can see the tomb of James Gallier, SR. on your left. Gallier was one of New Orleans most well known and prominent architects. This moment was placed here by his son. As you can see from the inscription James died tragically with his wife in a shipwreck in 1866. You can also see that he was born in Ireland, but what it doesn’t say is that his name originally was Gallagher. He changed it to the more French sounding Gallier possibly to appeal to the large French creole population in New Orleans. Unfortunately not all of his buildings have survived to modern times. His son James Jr. followed in his foot steps, he is the one the added this monument to his father. Some of the son’s more notable buildings include Gallier Hall (1845) and his home in the French Quarter which is open for tours.

Check out the symbols on the top of this tomb. It used to feature a bust of Dante but this was destroyed in Hurricane Katrina. Society tombs like this were very common in the 19th century and the Masons had (and still have) a large membership in New Orleans

Another society tomb, but this one is for Slavonian immigrants. Society tombs like this functioned in a similar way as life insurance works today. Members would pay a small fee to join, then a small monthly fee to maintain their membership. Then in the event of a death the society would pay out to the widow to cover burial expenses and if the family lacked a tomb the deceased would be buried in the society tomb. You can check out the numbers and the small stone vases at the base with family names. If you look to your left, you can see a marker honoring Croatian veterans.

Next on the tour is the Forchy tomb. Take note of the symbols on top of this tomb. First you have the statue of the young crying woman with a child. Symbols like this can be very personal and could symbolize the death of a child. Behind the statue is a urn with a cloak draped over it. Catholics did not allow cremation until Vatican II in the 1960s but Catholics (and other Christians) would still use the urn and the urn with a cloak draped over it as a symbol of loss and mourning because it was used by ancient Greeks and Romans. It is my belief that symbols like this give the grieving a bit of comfort and remind us all how universal death and mourning are.

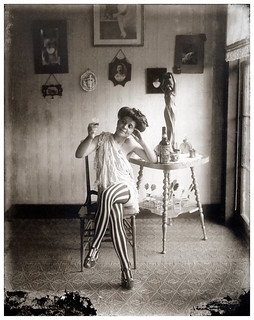

Bellocq was a photographer in the very early days of photography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While he photographed all sorts of subjects, he is by far most famous for his portraits of the women of Storyville. Storyville (1889-1917) was New Orleans red-light district where prostitution was legal and regulated. His photos offer our only real glimpse into this world and this era. His photos can be found in every book about this topic; in, fact you might recognize some of the more famous as they are often used as stock photos.

Take a close look at this tomb. Do you notice something? Around the flower symbols are the remnants of colorful paint. It was quite common in the 19th and early 20th centuries to paint your tombs bright colors. Yellow was a very popular color to paint your tomb, and this tomb probably had the flowers painted bright colors. Today it is very uncommon, even in restored tombs, to paint them bright colors even if it has been done traditionally, in the past.

Unfortunately many of these tombs have fallen into disrepair allowing you to see the brick and the shelf. Traditionally families would clean up, paint and leave flowers on All Saints Day (November 1st) but unfortunately, in more modern times this tradition has died out as families have disappeared or moved away and tombs become abandoned. There are organizations and nonprofits, such as Save Our Cemeteries, that have stepped in to try to save many of these tombs. You can help by donating to Save Our Cemeteries. Also avoid touching and disturbing these tombs, they are not movie sets but are the final resting place for the deceased.

This tomb is built in a style called stepped or stepped tomb as it resembles stone steps. Often this style is brick but this tomb is granite. Granite holds up better in the wet climate of New Orleans much better than brick, which might be why Florville chose this material as he was a stone cutter. His name is featured on the bottom in a small font on many of the marble slabs in this cemetery. He was also a freeman of color. He learned his trade from his father a native of France. His mother was a free woman of color. He was by all accounts a very prosperous man. Above his name you will notice poppies. Opium, the product of poppies, was a common 19th century treatment for many ailments including insomnia and became associated with a good night’s rest and your final rest, a sort of 19th century rest in peace.

These are a different style of tomb where the dead are placed below ground around four short walls and then either grass, gravel or cement is placed on the tomb. These tombs can get reused. You can see evidence of this from the multiple names and dates on the one on the left. This style might be used by a family who preferred to be buried underground, possibly for religious reasons.

Benachi was Greek and immigrated to New Orleans in the mid 19th century. He sadly lost his first wife and two children in the yellow fever epidemic of 1852. Yellow fever is a disease spread by mosquitoes and would plague New Orleans every summer until the early 20th century.This tomb is constructed partially out of cast iron. Look closely and you can see screws. Cast iron facades such as this one were very common on buildings in New Orleans and pretty much in every city in the USA in the 19th century. I’m not sure how common this was in tomb construction as this is the only example in this cemetery.

Check out the beautiful cast iron fence in front of this tomb. Decorative cast iron was a sign of wealth in the 19th century. You will see examples all over the French Quarter and other historic New Orleans neighborhoods. It was very common in every American city at the time but the cast iron New Orleans has survived

When you leave the cemetery and walk toward Bayou St John and City park you will see to your right the Wall Vaults. These were traditionally the more affordable option for burial in New Orleans cemeteries. Unfortunately these wall vaults have fallen into disrepair. Then you can continue on to check out City Park and the sculpture garden or take the Canal Streetcar back to the Quarter.